Philosopher

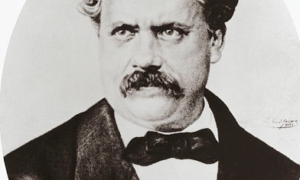

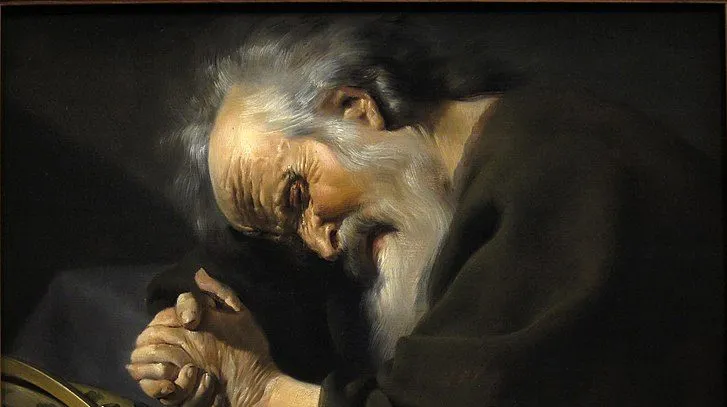

Anaximenes

Anaximenes biography

He was born in Miletus, in 590 b.C. According to Theophrastus, he was a disciple of Anaximander; and, in turn, Anaximander was a disciple of Thales. Anaximenes died in the year 524 b.C. Like his teacher, Anaximenes said that the origin of all things was infinite. This thought is due to the observation of Physis, the word that designates nature. The thought about the natural events propitiated by the desire of the pore gods little by little was displaced by the going of understanding of the gods on nature in contrast with the ignorance of the men. Anaximenes believed that the origin of all things was air, which generated existence with condensation and rarefaction. The philosopher understood the importance of other elements. The water and the fire. The first, created by condensation, generates clouds; the second, created by the rarefaction, generates fire. The condensation not only generated water but also everything that had a body: the clouds, falling, condense in earth and stones.

Through the thought and reflections of Anaximenes, it is considered as one of the three pillars that helped the birth of philosophy in the West. the line of Milesian philosophers, a name given to come from Miletus, is based on the abandonment of mythological thought. Religion became, for them, insufficient. The Miletus school based its research on the search or belief of the arche or aché. It is the substance that constitutes the whole; or, from which, all things start. Thales believed that this substance was water, Anaximander called the substance arche and established its main characteristics as infinity.

The work of Anaximenes, the Book of Nature, is only referenced by later authors. One of those authors is Diogenes Laertius. The main thought of Anaximenes relates to life. For him, the breath of life is air, the same air that holds us together embraces us. The infinite substance from which all things start, as well as in man, is the air, which surrounds everything and gives it meaning. This thought differs with his line of teaching by naming the infinity. The probable that this deduction is due to his experience. The air is present in the environment and helps the perception of the world for the different senses. Air is a vehicle in which sound and smell are transmitted, even perceived by touch. For Anaximenes, the earth was flat and had been created by the condensation of air. When the planet was created, the air, being breathed by the earth, began to warm up, thus giving rise to rarefaction. That second process created the fire that revolved around the earth giving rise to the stars.

The processes of change that are present in the air represent the functioning of the physis. The relationship that is established between the air and the cosmos is the same as the breath and the man; therefore, the cosmos is a macroscopic version of the man. This reflection provoked by the philosopher affects the Greco-Latin Renaissance, where the object of study is the human soul.

Aristotle considered the teachings of Anaximenes as shallow. The evidence that was attributed to the arche (infinite primordial element) was breathing. The air that entered the cold body, and came out hot. To put a mirror to check if someone had died just by looking if it got fogged up. All this represented to Aristotle an affirmation of naivety. For him, the human soul was not the breath of life, but the sensibility with which the world is perceived and understood. His work known as Peri Physeaos is lost. It was written in Ionic, classic Greek dialect belonging to Ionia. The reference of Diogenes Laertius tells us: “He wrote in Ionian dialect, in a simple and concise style”

Pliny the old says that Anaximenes was the first to observe the shadows that determine the change from day to night. The philosopher of Thales created, according to his observations, a kind of sundial called Sciothericon. These references can be found in book two of The Natural History that Pliny wrote. The chapter, LXXVI, that preserves said history refers to the artifact as “Umbrarum hanc rationem et quam vocant gnomonicen invenit Anaximenes Milesius, Anaximandri, de quo diximius, discipulus, primusque horologium, quod appellant, Lacedaemone ostendit.” A close translation would say: Anaximenes of Miletus, in the same argumentative line of Anaximander, of which we said was a disciple, was the first to create the clock, here in Lacedemonia.

Through the thought and reflections of Anaximenes, it is considered as one of the three pillars that helped the birth of philosophy in the West. The line of Milesian philosophers, a name given to come from Miletus, is based on the abandonment of mythological thought magical Religion became, for them, insufficient.

RECOMMENDED WORKS

Pre-Socratic Philosophers

Monism

Philosopher

Heraclitus

Biography of Heraclitus

Heraclitus (540 BC – 470 BC) was a pre-Socratic philosopher considered one of the founders of Greek metaphysics. He was born in Ephesus, Greece, which was located in Ionia on the western coast of Asia Minor (present-day Turkey). It is said that he came from an ancient aristocratic family. He inherited political ideas from his family that were at odds with the democratic Athenian style, and Heraclitus sympathized with Persian King Darius I the Great. His enigmatic character earned him the nickname “the Dark One of Ephesus.” It is known that he wrote a book called On Nature, which was divided into three parts: the universe, politics, and theology. However, there is no evidence of this work, and what we know about this philosopher comes from fragments, interpretations of other philosophers of the time, quotations, references, and comments.

However, the appearance of complete aphorisms suggests that his style of thought was oracular. This has led some to believe that Heraclitus did not write any texts, following the idea that his teachings were purely oral. In this sense, the work of his disciples may have been to record his postulates in the form of sentences. Heraclitus explained natural phenomena by attributing an important role to fire, and he claimed that fire is the source of everything. For the Greek, fire would be the archetypal form of matter, because it has the ability to change everything.

“This world, which is the same for all, was not created by any of the gods or men, but has always been, is, and will be an eternal fire that is ignited according to a regular order and extinguished according to a regular order” – Heraclitus.

Heraclitus: fire and perpetual becoming.

Fire is the creator of the common constituent of all things and the main cause of all the changes that occur in nature. If we talk about the elements of nature, following Heraclitus, it would be in order: fire, air, water, earth. In addition, the Greek stated that Everything flows and nothing remains. Something very important is that the Greek conceived a universe in perpetual becoming. The engine of that eternal mutability is the opposition of opposites; such opposition is the cause of the becoming of things. In short, if health did not exist, there would be no illness, and so with satiety and hunger, day and night, life and death or good and evil: they are interdependent. The balance of the universe is maintained thanks to the continuous relationship between opposites, which gives rise to changes that compensate each other reciprocally, this will ensure that change in one direction will eventually lead to another change in the opposite direction, avoiding chaotic preponderance and maintaining the total stability of the cosmos.

“No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it is not the same river and he is not the same man.” – Heraclitus.

Logos

The theory of logos by Heraclitus can be interpreted as an internal harmonious law that reveals the coherence and balance of the universe. To be a wise man, it is necessary to understand this internal logic, since wisdom consists in understanding how the world works. This understanding must be the basis of moderation and self-knowledge, which Heraclitus considered as ethical ideals for man. His thought was studied by Parmenides, who claimed that the existing is one and immutable, in contrast to Heraclitus’s theory that everything is change and incessant becoming. This classic antinomy in Greek philosophy laid the foundations for the development of metaphysics and dialectics.

It is said that the death of the Greek philosopher Heraclitus was caused by dropsy, an affliction that would have been caused by his misanthropy and his retreat to the mountain, where he fed exclusively on herbs. Heraclitus was one of the great philosophers who contributed to the growth of Greece. He shared the idea of Tales of Miletus that explanations about the creation of the universe should not be sought in religion or in the gods, but that man had the ability to give a rational explanation to what was happening around him.

The main contributions of Heraclitus.

The main contributions of Heraclitus center on the theory of fire as the fundamental element, the mobility of the universe, duality and opposition, and the principle of causality. According to him, everything has a cause, but not everything has the same cause. He also developed the theory of logos, understanding that this element was incomprehensible to man, although it was always present. Although everything constantly changed, that did not mean that there was no order, and in that sense, the logos was part of this order. Indirectly, Heraclitus also provided some tools to determine and understand a society, and exposed questions related to the ideal state of things.

Plato contributed decisively to forge the image of the philosopher, and after Parmenides and Heraclitus, other thinkers tried to reach an eclectic synthesis, for example, pluralists like Empedocles tried to transfer the immutability of being exposed by Parmenides to elements such as the four elements, Anaxagoras did it to homeomerias, and atomists to the atom. However, the eternal becoming of Heraclitus was always present, in one way or another, in the forces that combine and govern these elements.

Although Heraclitus was unpopular in his time and despised by later biographers, his main contribution was his understanding of the formal unity of the world of experience. In modern times, Hegel was inspired by his thought in developing the theory of becoming deeply.

Heraclitus’ phrases

- “It is granted to every man to know himself and to meditate wisely”

- “An abundance of knowledge does not teach men to be wise”.

- “God is day and night, winter and summer, war and peace, hunger and satisfaction. And changes like fire”.

- “In the circle, the beginning and the end are confused”.

- “It is necessary to know that war is common and justice is discord, and that everything happens according to discord and necessity”.

- “The soul is stained with the color of its thoughts. Think only of those things that are in line with your principles and that can see the light of day”.

Philosopher

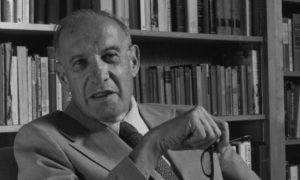

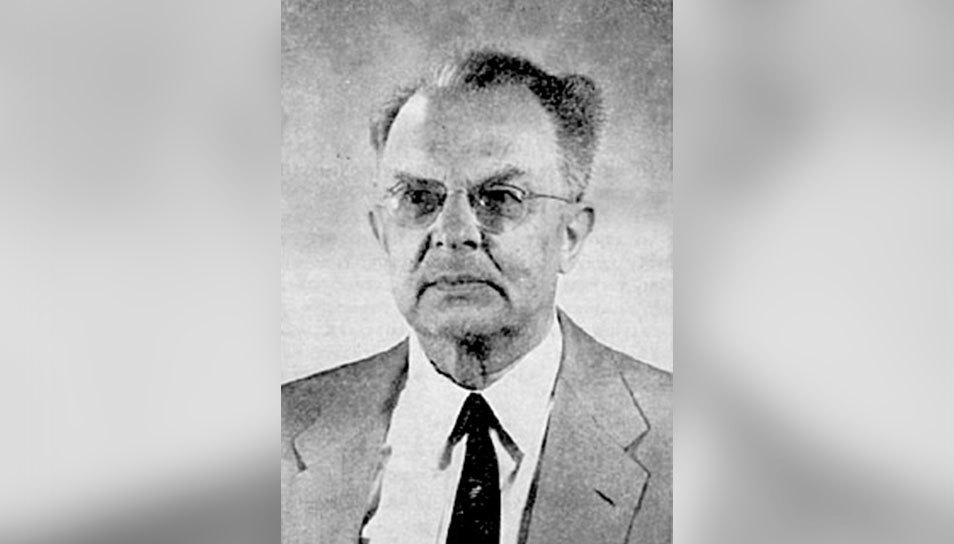

Rudolf Carnap

Rudolf Carnap Biography

Rudolf Carnap (May 18, 1891 – September 14, 1970) was born in Ronsdorf, Germany. German philosopher, one of the most important exponents of the Vienna Circle, a philosophical collective formed by Moritz Schlick, in which the philosophers Kurt Gödel and Otto Neurath stood out. Throughout his career, Carnap served as a professor of philosophy in different universities (Vienna and Prague). Before World War II broke out, he moved to the United States, where he continued teaching in Chicago, Princeton, and Los Angeles. For his contributions concerning neo-positivism, the construction of logical systems and discourse analysis is considered one of the most relevant philosophers of the twentieth century.

Early years

Son of Johannes Carnap and Anna Dorpfeld. Carnap was born into a modest German-Western family, which provided him with a good education. He began his academic training at the Barmen Gymnasium. Between 1910 and 1914 he studied philosophy, mathematics and traditional logic at the universities of Jena and Freiburg. While studying at the University of Jena he was a disciple of the mathematician Gottlob Frege, who at that time was known for his studies on mathematical logic, becoming seen as one of the most prominent exponents of his time; Frege’s work profoundly influenced Carnap’s studies.

After the outbreak of the First World War, he entered the University of Berlin, where he continued his philosophical training. Later he obtained his doctorate at the University of Jena with the thesis on the concept of space, which he divided into three types: space physical, intuitive space, and formal space. Since then he began to carry out research in which he addressed topics such as time and causality, and also discussed theories of symbolic and physical logic.

Carnap and the Vienna Circle

Towards the end of the 1920s, he began to work as a professor of philosophy in Vienna, at which time he associated with the Vienna Circle.Philosophical collective founded by the empiricist logical Moritz Schlick, who invited Carnap to participate in meetings and studies of the circle. At that time the group was trying to create a scientific perspective of the world, through which the rigor of the exact sciences could be applied in philosophical theories and their studies, an idea that contrasted with the philosophical approach of the time, which was carried out Verifications based on deductions through an unofficial or strict language, which opened space for any doubts.

In 1929 the circle presented the manifesto The scientific conception of the world: the Vienna Circle, written by Otto Neurath. This showed the signatures of Carnap and Hans Hahn. In the manifesto the circle set out the principles of neo-positivism and its opposition to meaningless metaphysics, emphasizing the importance of verifiability; these approaches were inspired by the work of Wittgenstein Tractatus logico-philosophicus (logical-philosophical treatise).

During this period the philosopher delved into the philosophical problems and the language with which they are addressed. Because these problems derived from the inappropriate use of language, to test this approach he carried out various studies in which he tried to build logical systems that were capable of avoiding ambiguities and misuse of language. In parallel, he focused on analyzing scientific discourse, among the most outstanding works that addressed these themes are: The logical structure of the world (1928), the overcoming of metaphysics through the logical analysis of language (1931) and The logical syntax of the language (1934). Towards the middle of the 1930s, he moved to the United States, motivated by the rise of Nazism in Germany. When he settled down, he began working as a professor at the University of Chicago, an institution where he worked until the early 1950s.

In these years he wrote Investigations in semantics (1942-47), Meaning and necessity (1947) and Logical foundations of probability (1950). In the first two books he studied the formal and conceptual aspect of language and in Logical Foundations of the probability in which he distinguished between statistics and logic, generating important contributions in the field of statistics. Between 1952 and 1954 he taught at Princeton, followed by moving to California where he was hired as a professor at the University of California. He worked until the 1960s.

In the last years of his career, Carnap published Introduction to Symbolic Logic (1954), Philosophy Della Scienza: anthology (1964) and Philo Foundations Of Physics (1966), among others. Throughout his academic career, Carnap defended and promoted the principles of mathematical logic or symbolic logic, through which he tried to create a scientific perspective of the world.

After a long and outstanding academic career Carnap, he died on September 14, 1970, in Los Angeles, California.

Philosopher

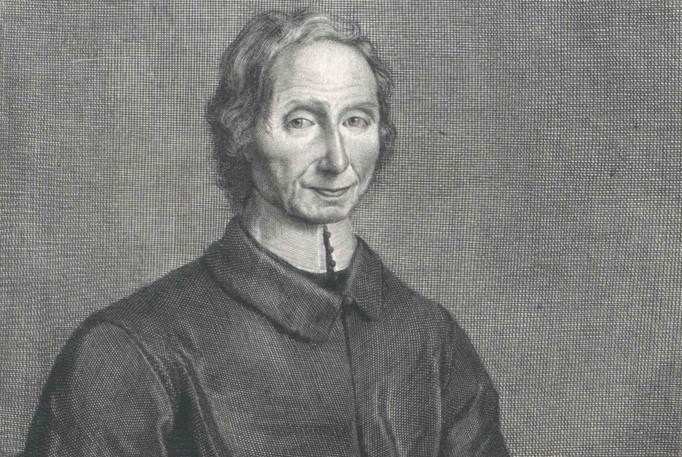

Nicolás Malebranche

Nicolás Malebranche Biography

Nicolás Malebranche (August 6, 1638 – October 13, 1715) was born in Paris, France. Philosopher and theologian considered one of the most relevant thinkers of his time. Malebranche was one of the followers of the thought of Rene Descartes, whose work he read avidly. Eventually became one of the main drivers of occasionalism, a doctrine created by the followers of the French philosopher. Malebranche revitalized the doctrine by including ideas based on Augustinianism.

According to this philosophy, the body and the mind are separate entities, which are connected by the intervention of God, also, for these the cause-effect relationship is determined by divine intervention, turning the cause into an occasion for God to act. His most outstanding works are The search for truth (1674-1675) and Christian and metaphysical meditations (1683).

Early years

Son of Nicolás Malebranche and Catherine de Lauzon. His father was a prominent public official. Malebranche was the last of the couple’s twelve children. During the first years of training, he received a deep religious education from his mother, which influenced his personality, reflective and collected. At that time, he studied at the school of La Marche and years later he entered La Sorbonne, where he studied theology and philosophy between 1656 and 1659.

Subsequently became interested in the religious vocation, thus joining the congregation of the Oratory as a novice, decision it is believed that was influenced by his character and the loss of his parents in the early 1600s. During the novitiate, Malebranche, concentrated on meditation and spiritual development. After a few years of taciturn life he was ordained a priest in September 1664.

After being ordained, he devoted himself to the study of various topics. Practice that was in tune with the principles of the Oratorium, a center in which the religious, in addition to focusing on their religious work, carried out various investigations related to cultural and historical issues. The first studies of Malebranche, were on the history of the oriental languages and the history of the fathers of the Church (patristic).

For this same period, he became interested in the life and work of St. Augustine, a religious on which he wrote various works. Also, he studied and interpreted the sacred texts, however, these subjects did not seem to be passionate. On the contrary, it happened with the work of René Descartes. When he read the Treaty of Man he became interested in all the work of the French philosopher, which he studied in detail, deeply analyzing each work. At that time, he studied mathematics, physics, and physiology. Based on this new knowledge, he analyzed the Cartesian and Augustinian works.

Work by Nicolás Malebranche

The first book of the philosopher was The search for truth (1674), a work in which Malebranche delves into the spirit, his relationship with the body and God, emphasizing the importance of the relationship between the spirit and God. In this criticism of pagan and Christian philosophers, for not delving into these relationships, he also proposes as a task of philosophers to highlight the connection between God and the spirit, an idea that is linked to the occasional doctrine; a short time later he published the other two volumes of the book.

Two years later, he published Conversations chrétiennes, (1676), followed by the Treaty on Nature and Grace (1680), a treaty he wrote after discussions he had with Father Arnauld. This work delved into topics such as creation, incarnation, divine grace, and human freedom. After its publication, it was harshly criticized since it had tried to solve insoluble problems of religion by harmonizing various concepts so that the divine plan and God’s handling of all things were understood. Given the theme that he dealt with, it was quickly included in the Index. In the following years, he published the Treaty of moral and Christian and metaphysical Meditations (1683) and Entretiens sur la métaphisique (1688).

At the end of the 1690s, he wrote and published Entretiens sur la mort (1696), a book that revolved around conversations and ideas about the death of three men, one thinks that life is too short, another that it is too long and the last more spiritual and conscious about the experiences he has had raises that death only expands our minds. This work is based on the near-death experience the philosopher lived when he became seriously ill. A year later he published the Treatise on the Love of God (1697), as the name implies, this treatise speaks about the love of God, emphasizing how man is drawn to love him and how this produces happiness.

Two years later, he was appointed honorary member of the French Academy of Science, for his contributions in the field of mathematics. His last work was Conversation of a Christian philosopher and a Chinese philosopher (1708), a book in which he deals with themes such as the existence of God and the nature of it, seen from two perspectives. The work of this philosopher was criticized by various writers and religious of the time such as Father Arnauld, Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet, and François Fénelon, among others. The renowned philosopher and religious died on October 13, 1715, in Paris.

Philosopher

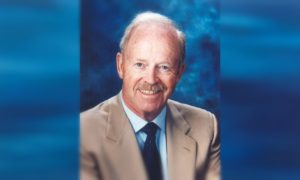

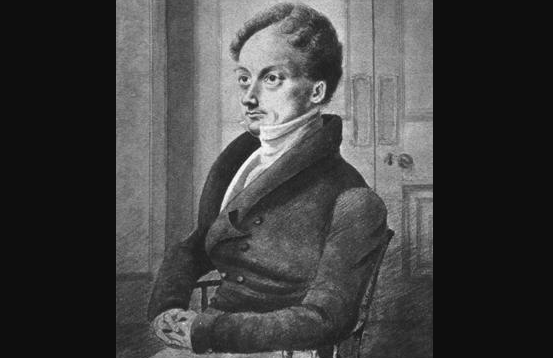

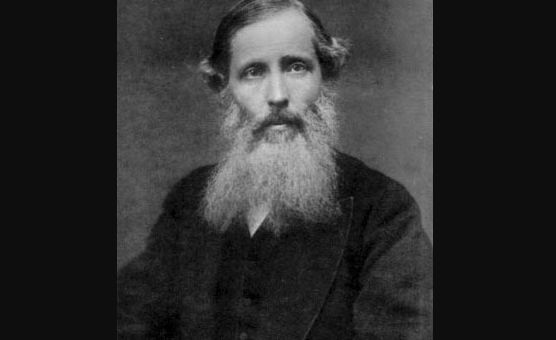

James Mill

James Mill Biography

James Mill (April 6, 1773 – June 23, 1836) was born on Northwater Bridge, Scotland. Philosopher, a historian, and British economist considered one of the most relevant figures of the 19th century. Mill was a brilliant and influential scholar. His thinking and the ideas he promoted changed the way in which political theories on human rights and equality were understood, throughout his career, he rejected the actions of the East India Company in the colony. He was one of the main drivers of utilitarianism, a philosophical theory created by Jeremy Bentham, an economist with whom he worked for several years.

Throughout his career, he wrote for the Anti-Jacobin Review, the British Review, the Eclectic Review, and the Edinburgh Review. Among his most outstanding works are Principles of political economy (1822) and Analysis of the phenomena of the human spirit (1829). Mill was the father of the renowned philosopher and utilitarian economist John Stuart Mill.

Studies

Mill studied at the University of Edinburgh, where he stood out for his intelligence, becoming one of the institution’s outstanding students. In 1798 he graduated as a Presbyterian preacher, a profession he practiced on an itinerant basis. At the same time, he started teaching. While teaching, he became interested in historical and philosophical studies, areas in which he deepened the rest of his life.

Career

Towards the beginning of the 19th century, he moved to London, where he served as a journalist. At that time, he published a booklet in which he talked about the corn trade, criticizing the reward given for the export of grain. In 1803, he was in charge of the London Literary Journal and two years later he was director of the St James ’Chronicle. The following year, he began to write History of British India (1817), a work in which he delved into the history of India based on the information collected in recent years by English-speaking writers, it consisted of three volumes divided into six books.

In the first book, he deals with the first interactions between Great Britain and India, the second book talks about religion, literature, and culture of ancient India. The third book, talks about the Islamic conquest and the government and the last three deal with the expansion and consolidation of the British government in India, emphasizing the operation of the East India Company, a company that criticized extensively.

In 1808, he came into contact with the economist and philosopher Jeremy Bentham, with whom he shared interests and ideas, becoming allies and fellow students. In the following years Mill adopted the principles of utilitarianism, which he helped spread. Between 1806 and 1818 he collaborated in several publications such as the British Review, the Anti-Jacobin Review, the Edinburgh Review, and the Eclectic Review. He was also editor and writer of the Philanthropist newspaper with William Allen, a publication in which he contributed articles on education, laws, and freedom of the press.

For this same period, he wrote articles on politics, education, and law for the Encyclopædia Britannica, which were published in the appendix of the fifth edition of 1814, among which were highlighted Prisons, Jurisprudence, and Government, articles that were reprinted on several occasions and influenced deeply in the political environment of the time, which was reflected in Parliament’s reform project in 1832.

After harshly criticizing the East India Company in his book History of British India (1817), he was appointed official at the House of India in 1819, a position he served for several years; over time it was climbing positions, becoming head of the examiner’s office in 1830. During these years he promoted various reforms that changed the way the colony was governed. At the beginning of the 1820s, he published Principles of Political Economy (1822), a book in which he presented his theory of the salary fund, which is directly related to supplying and demand. This was further developed by his son, John Stuart Mill. In this work, the influence of economist David Ricardo’s thinking can be seen.

In the following years, he participated in the discussions that led to the foundation of the University of London in 1825. Four years later, he published Analysis of the phenomena of the human spirit (1829), a work in which he applied the utilitarian premises to psychology, proposing a theory of the human mind based on the foundations of associationism.

In the last years of his career, he published Essay on the Ballot and Fragment on Mackintosh (1830) and Whether Political Economy is Useful (1836). Mill’s work profoundly influenced the country’s politics, especially in the reform of Parliament, as well as in the change in the way the colony was governed.

It is necessary to highlight that his work History of British India (1817), written without him visiting the country, created an unfavorable image of India, which was seen by readers as an extremely backward and underdeveloped country. The renowned British scholar and economist died on June 23, 1836, in Kensington, London.

Philosopher

Henry Sidgwick

Henry Sidgwick Biography

Henry Sidgwick (May 31, 1838 – August 28, 1900) was born in Skipton, England, United Kingdom. Philosopher and economist, founder of the Psychic Research Society, of which he was also president. Sidgwick is one of the most prominent utilitarian philosophers of the 19th century. The creator of the theory of international values, which he developed in his most recognized work is Principles of political economy (1883). Throughout his professional career, he worked as a professor at Trinity College and Knightbridge. In parallel, he conducted various research on ethics, morals, and economics. He was a follower of the ideas of John Stuart Mill and Immanuel Kant, which are reflected in his work. Sidgwick was one of the intellectuals who promoted higher education for women through Newnham College.

Early years

Son of the Reverend William Sidgwick, who was a descendant of a family of cotton makers, which had settled in Yorkshire. Two years before Sidgwick’s birth, the Reverend was hired as the principal of Skipton Elementary School, a position he held until 1841, the year he died, at which time Henry Sidgwick was only three years old. Sidgwick was educated at home until 1848, at which time he began attending Bishop College, then left home to join his brothers in a school located Blackheath, which was under the direction of Pastor H. Dale. During the following years Sidgwick, stood out for his talent and intelligence, which is why his mother aware of his abilities decided to provide the best education, so he sent Sidgwick to Bristol, where he went to school, a short time later the family settled in Bristol.

Studies and professional career

In the mid-1850s, he left the family’s home to study at the university where his father had graduated, Trinity College, in Cambridge, where he studied Mathematics and Human Sciences. During this training stage, Sidgwick was a member of the Cambridge Apostles, a society with a great reputation in the alma mater, in which several debates are held on various topics, in which each member writes annotations, which are preserved and passed on to being part of the archives of the society. After graduating the members of the society are called Angels, and sometimes they attend meetings of the society. After standing out among the students of his course, Sidgwick obtained his degree in 1859, that same year he was elected member of Trinity College, later he was appointed professor of classics, a class that changed by Moral Philosophy in 1869.

In the course of the 1870s, he gave various conferences for women, later named the Newnham College, an institution for women which was managed in the early years by Anne Clough. Three years later, he published his first book, entitled The Methods of Ethics (1874), a book in which the influence of Mill and Kant’s work is reflected, in this he proposed a method that allowed ethical decisions to be made based on three approaches: selfishness, utilitarianism, and intuitionism.

The first refers to the theory that justifies a certain action if it produces happiness to the person who performs it, regardless of whether it can affect others. Utilitarianism tries to contribute to the happiness of all the people involved and intuitionism takes into account other purposes besides happiness. In the end, the author mentions that selfishness and intuitionism do not provide an appropriate basis for rational behavior, so he proposed a system that reconciled selfishness and altruism, without neglecting British ethical utilitarianism.

In 1875, he was elected preselector of Trinity College. The following year he married Eleanor Balfour, who became the director of Newnham College in 1892. At the beginning of the 1880s, she became a member of the Metaphysical Society and began to be interested in psychic phenomena, which led him to found the Society for Psychic Research in 1882. Edmund Gurney, and Frederic William Henry Myers participated, among others. A year later he published Principles of Political Economy (1883), his most famous work, in which the author developed a theory of international values. That same year he was appointed Professor of Moral Philosophy at Knightsbridge. In the following years, he published The scope and method of economic science (1885), followed Outlines of the History of Ethics for English Readers (1886).

In the last decades of his life, he published Elements of politics (1891) and Practical Ethics (1898). After his death, Philosophy: its Scope and Relations (1902) was published as well as the development of European politics (1903), Miscellaneous Essays and Addresses (1904) and Lectures on the Philosophy of Kant and Other Philosophical Lectures and Essays (1905).

Until 1900 he continued working at Trinity College, an institution in which he had a prominent position, and also actively participated in the reform of the institution. The famous philosopher and economist died on August 28, 1900, in Cambridge, England.